Treatement of Depression Among Peaple Life With Hivaids on Art

Abstract

As in other sub-Saharan countries, the burden of depression is high among people living with HIV in Republic of malaŵi. However, the clan between depression at ART initiation and two critical outcomes—retention in HIV care and viral suppression—is not well understood. Prior to the launch of an integrated depression handling program, developed patients were screened for depression at ART initiation at two clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi. We compared retentiveness in HIV care and viral suppression at 6 months between patients with and without depression at ART initiation using tabular comparing and regression models. The prevalence of low among this population of adults newly initiating ART was 27%. Those with low had like HIV care outcomes at half-dozen months to those without depression. Retention metrics were more often than not poor for those with and without depression. However, among those completing viral load testing, nearly all achieved viral suppression. Depression at ART initiation was not associated with either retention or viral suppression. Further investigation of the relationship between depression and HIV is needed to empathize the means low impacts the different aspects of HIV care engagement.

Introduction

The prevalence of HIV in sub-Saharan countries such as Malawi are among the highest in the globe [i, 2]. Like many other countries in the region, Malawi, has adopted a "public wellness arroyo" to HIV calibration-up in order to meet the UNAIDS 90-90-ninety goals (diagnosing xc% of all people living with HIV, providing antiretroviral therapy [Art] to xc% of those diagnosed, and achieving viral suppression for xc% of those treated) [three,4,5]. Not bad strides have been fabricated towards achieving these goals and engaging people living with HIV in care across the region [6, 7]; in 2018 in Malawi, ninety% of those living with HIV were estimated to exist enlightened of their status, 87% were on treatment and 89% were virally suppressed [1]. Despite recent improvements in Art service provision, both linkage to care and continued engagement in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remain challenging [8, 9]; improving retention in HIV care will be crucial to attaining the ninety% on ART target in the sub-Saharan region [viii, 10]. The reasons for attrition among people living with HIV are not entirely understood, though barriers to retention in intendance may include human resource and institutional challenges, distance to the clinic, lack of support, stigma and fright of HIV status disclosure, and psychiatric illnesses such as depression [11,12,thirteen,14].

Low is a major contributor to the burden of disease and inability and is highly prevalent amid people living with HIV in Malawi and elsewhere in SSA, a region where mental health care is often limited [xv, 16]. Depression affects eighteen to 30% of patients receiving HIV care in Africa [17], and estimates from Republic of malaŵi range from i to 19% [eighteen,19,20,21]. The high prevalence of depression among people living with HIV is thought to be due to coping with the HIV diagnosis, disease symptoms, bereavement, human relationship crises, stigma and discrimination, co‐existing poverty, ART side furnishings, fear of decease, and infection-related inflammatory processes [22, 23]. Depression can result in reduced quality of life, decreased economic productivity, social isolation, and cognitive reject [22, 23]. Among people with HIV, depression has the potential to worsen HIV-related morbidity and mortality, particularly in low-resource settings.

Depression has been shown to be an important bulwark to linkage to intendance, retention, Art adherence and ultimately long-term viral suppression across the globe [17, 24,25,26,27,28,29]. A bourgeoning body of research in SSA is beginning to demonstrate that depressed individuals are less likely to exist linked to ART care or start Fine art [30,31,32]. Further, depression is likewise associated with poor adherence to Art in SSA [17, 24, 33]. Still, limited research has been conducted in SSA on the association between depression and consistent retention in HIV care and viral suppression. As such, farther evidence is needed to characterize the association between low, HIV care engagement, and achievement of viral suppression is the sub-Saharan region.

This assay addresses this knowledge gap by generating evidence on the association of depression with two central HIV care outcomes: retention in HIV care and viral suppression. Compared to those without depressive symptoms, we hypothesized that those with elevated depressive symptoms at Art initiation would be less likely to be retained in HIV care and to be virally suppressed 6 months afterward ART initiation.

Methods

Study Design

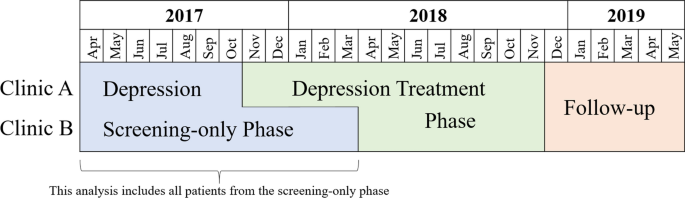

This study is nested within the beginning phase of a airplane pilot plan that integrated low screening and handling into routine HIV master care using existing staff at two public health clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi. We implemented this programme in 2 staggered phases—a depression screening-but phase and a depression treatment intervention phase [34]. This study focused on individuals who initiated Art during the screening-only phase (Fig. 1).

Plan implementation

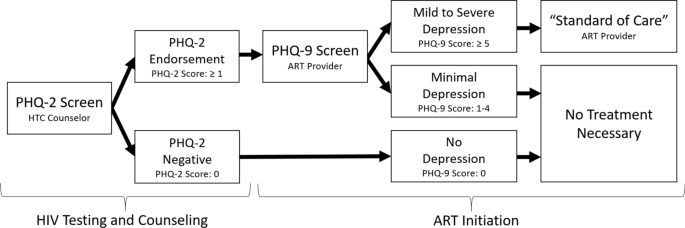

During the screening-merely phase, HIV testing and counseling (HTC) counselors and ART providers screened patients for depression at ART initiation using the Patient Wellness Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-ix). The PHQ-9 is a nine-item questionnaire that assesses the presence and frequency of the ix Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders symptoms of major depression [35]. It has been widely used in the sub-Saharan region [36,37,38]. HTC counselors screened all patients newly diagnosed with HIV for depressed mood or anhedonia using the first two questions of the PHQ-9 known as the Patient Wellness Questionnaire-two (PHQ-ii). For patients who endorsed at least one of the PHQ-2 questions, the Art provider so administered the remaining seven PHQ-9 questions during Art initiation. A total score of 5–9 and ≥ 10 are considered indicative of balmy low and moderate to severe depression, respectively [39]. Patients who were identified with elevated depressive symptoms were managed by providers using existing "standard of care" options within the Malawi primary care arrangement. (Figure ii) These options theoretically included counseling, antidepressants or referral to an on-site or off-site mental health specialist, or in acute cases, transport to the outpatient psychiatric unit at the nearby district hospital. However, in practice counseling consisted of breezy counseling by the ART provider and antidepressants were rarely prescribed (and when prescribed, often at sub-therapeutic doses). In theory, the ART providers could have used the treatment program's evidence-based protocol to prescribe antidepressants or refer patients for evidence-based counseling at follow-upwards appointments during the treatment phase, although we identified only a few instances when this occurred.

Depression screening process

Population

All non-pregnant adults (xviii years or older) newly initiating ART at the study sites were eligible to be enrolled in the program evaluation. Research administration approached such individuals awaiting ART initiation to invite them to participate in the study and nearly all (96%) provided informed consent. This analysis is restricted to consenting individuals who completed depression screening during the screening-just phase of the program, e.thou. only those who initiated care between April 2017 and October 2017 at Clinic A and betwixt Apr 2017 and March 2018 at Clinic B (Fig. i).

Data Drove and Abstraction

This report relied on the abstraction of routinely collected clinical data on depression screening and HIV care from consenting participants' Fine art clinical records over a 13-month menstruum, starting at ART initiation. At the study sites, when a patient initiates Art, clinic staff create a newspaper medical nautical chart (called an ART mastercard) and accompanying electronic medical record for the patient where HIV care data will be recorded. At each date, the clinicians schedule the next follow-up date and provide the patient with a supply of ART that will last until their next appointment. ART pills are provided in increments of 30. Generally, for the first half dozen months of care, newly initiating Art patients are scheduled to come monthly, though exceptions tin be fabricated and a larger supply of Art tin can be provided.

Measures

Depression at ART Initiation

Elevated depressive symptoms suggesting a loftier risk of a depressive disorder (hitherto described as "depression") was defined as a PHQ-nine score ≥ 5 at Fine art initiation, post-obit the definition in the parent study [xl]. We also consider a three-level categorical depressive severity measure (0–4, 5–nine, and ≥ x, corresponding to no, balmy, and moderate to severe low, respectively).

Viral Suppression

We defined viral suppression as a viral load < 1000 copies/mL drawn at least 5 and a half months (166 days) subsequently starting ART, following the 2018 Malawian Art guidelines. Viral load testing was performed at Bwaila Hospital in Lilongwe using collected plasma or dried blood spots and processed by Abbott m2000 RealTime HIV-i assay instruments [41].

Retention in HIV Intendance

We constructed several measures to capture retention in HIV care through half dozen months in care. Some measures were constructed specifically for this analysis, while others were constructed in alignment with nationally and internationally recognized measures of retention.

Continuous engagement in care was defined as never beingness more that 14 days late to an appointment through 6 months in intendance.

"Alive and in care" at 6 months was defined as beingness on ART for at to the lowest degree some portion of the 2 months prior to the 6-month ceremony of starting Fine art, in alignment with Malawi Ministry of Wellness reporting practices. Co-ordinate to the Malawi Guidelines for Clinical Direction of HIV in Children and Adults, an Fine art patient is classified equally a "defaulter" if they go 2 months without ART based on the pills provided at their almost contempo appointment [42]. Patients who are not known to have transferred, stopped Art, or died are classified equally "live and on ART."

Currently on ART at 6 months was defined as currently having Fine art on hand at 6 months, i.eastward. attending an appointment prior to the 6-month point and receiving a supply of ART that would last through the half-dozen-calendar month point. For example, if a participant attended an appointment 5 and half months later starting ART and received a 30-day supply of ART, they would have been considered "currently on ART" at 6 months. This indicator aligns closely with the PEPFAR definition of "currently on treatment" [43].

In intendance later 6 months was defined equally attending at least one appointment where ART is provided after half-dozen months in intendance. This definition aligns more than closely with the UNAIDS Global AIDS Monitoring 2019 Indicators by identifying participants known to be on ART at some point 6 months after initiation [44].

HIV appointment omnipresence was defined as the proportion of scheduled HIV appointments attended within one week of the scheduled appointment date in the first 6 months of care [45].

Consequent Art was defined as never going more than than 5 days without ART in the first half dozen months, calculated from the cumulative days' supply of Fine art dispensed at each date in the first 6 months and the time between appointments.

ART pill possession ratio was defined equally the proportion of the first 6 months (183 days) since Fine art initiation with Fine art in hand, calculated from cumulative pills dispensed at each Fine art date through 6 months [46].

Retention + Viral Suppression

A combined consequence of continuous engagement in HIV intendance with viral suppression half-dozen months after starting ART was divers as meeting both of the following criteria: never being more 14 days late to a scheduled HIV appointment through 6 months in care and having a viral load < yard copies/mL drawn at to the lowest degree v.5 months (166 days) after ART initiation.

Variables of Involvement

Due to the data collection blueprint of this study, only routinely nerveless clinical data was captured including age, sex, clinic, World Wellness Arrangement (WHO) HIV clinical stages for HIV surveillance [47], village of residence, and ART medication prescribed. Village of residence was used to categorize individuals equally residing in urban Lilongwe Metropolis, in rural Lilongwe District or outside of Lilongwe Commune. Baseline CD4 and viral load are non collected in the Republic of malaŵi public health arrangement as the policy encourages a 'test and treat' strategy; individuals who test positive for HIV are initiated on ART irrespective of CD4 and viral load.

Analysis

We first completed unadjusted, tabular comparisons of HIV care outcomes by depressive severity (none, mild, and moderate to severe). Nosotros then used log-binomial models to estimate adjusted risk ratios comparing the probability of each binary HIV intendance outcome amongst those with depression compared to those without. For the continuous outcomes, we used ordinary least-squares linear regression models to estimate mean differences. Potential confounders were identified through directed acyclic graph (DAG) analysis.

To address missing outcome data for those who transferred to a not-study facility or who returned for care around vi months only did not get a viral load, we used multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) to fill up missing values using logistic regression imputation methods [48]. Assuming this data was missing at random (MAR), we imputed values based on the covariates included in the final model. Nosotros generated fifteen imputed datasets to ensure the number of imputed datasets was at to the lowest degree as big every bit the percent of incomplete information for the main outcome, "continuous appointment with viral suppression"[49]. Finally, we confirmed that the number of imputed datasets was also larger than the parameter-specific fraction of missing information for all parameters included in the final model [50].

All analyses were performed using STATA IC 14.

Ethical Review

The National Health Sciences Enquiry Committee of Republic of malaŵi (NHSRC) and the Biomedical Institutional Review Lath (IRB) of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill canonical the report protocol. All participants underwent a consent process during Fine art initiation and gave written informed consent to allow the abstraction of their clinical data. During the consent process, the research assistants explained that participation was voluntary, would not touch on care provided at the facility, and would not be necessary to receive ART.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of 1091 participants screened, 602 (55%) screened negative on the PHQ-two; the full PHQ-9 was administered to the remaining 489. (Tabular array 1) Of these, 290 (27% of those enrolled) endorsed symptoms consequent with our operational definition of depression (PHQ-9 score ≥ 5). Of these, 74% had balmy depression (PHQ-ix scores 5–9) and 26% had moderate to astringent depression (PHQ-nine scores ≥ 10). The nigh normally recorded depression handling was breezy "counseling by the Art provider." Nevertheless, a total of 16 individuals with depression were prescribed antidepressants, xiii of which started a sub-therapeutic dose. Only 2 of these individuals were prescribed antidepressants more than once. None of the participants were ever referred for evidence-based counseling and but six individuals were always prescribed antidepressants at a follow-upwardly visit. Just over half of all participants were female; those with depression were slightly more likely to be female than those without. The hateful historic period of participants was 33.5 years and did not vary appreciably between participants with and without depression. Nigh all participants were classified as asymptomatic (Stage I) for HIV at ART initiation and were initiated on a combination of tenofovir, lamivudine and efavirenz (TDF/3TC/EFV).

HIV Care Outcomes: Retention in Care and Viral Suppression

The HIV intendance outcomes measures did non vary appreciably between those without, with mild, and with moderate to astringent depression (Table 2). Effectually 7% of participants transferred (n = 72) or died (n = 2) within the first 6 months of care and thus had missing event data for every metric. Regardless of metric, retentivity in HIV intendance was generally low. Using the Republic of malaŵi Ministry of Health Fine art patient classification, around sixty% of participants would have been classified every bit "alive and in care" at 6 months and attended an appointment after six months. Effectually l% were currently on Fine art at 6 months and around 40% maintained a consequent supply of Fine art through 6 months. There was also substantial missing viral load information every bit only 45% (N = 454) of patients who had not transferred or died had viral loads drawn. Of those with viral load information, most all were virally suppressed. Only around 21% of participants achieved both continuous engagement and viral suppression, though an boosted 7% (n = 72) accomplished continuous date, just had missing viral load data.

The final adjusted model controlled for clinic and sex activity. As a continuous variable historic period introduced model instability and was removed from the last adjustment set as age did not appear to be associated with any of the outcomes or low at baseline. WHO phase, Fine art medication, and area of residence did not vary plenty to be considered potential confounders. Addressing missing data through multiple imputation did not appreciably alter whatever of the results.

After adjustment, all the estimates for the human relationship between balmy to astringent depression at Art initiation and HIV care outcomes were both close to the zilch and had 95% confidence intervals that spanned the null. (Table iii) Sensitivity analyses treating depression every bit a categorical variable (no, balmy, and moderate to severe low) and every bit a binary variable comparing moderate to severe depression (PHQ-nine ≥ ten) to no to mild depression (PHQ-nine < 9) yielded like results.

Discussion

While the prevalence of depression among this population of adults newly initiating ART was loftier at 27%, those with depression had similar HIV care outcomes at 6 months compared to those without depression. Memory metrics were generally poor for both groups. Even so, among those sent for viral load testing, nearly all achieved viral suppression.

The influence of low on retention in HIV intendance is complicated. Several recent reviews and meta-analyses have documented the association between depression and ART adherence [24, 51], though the human relationship between depression and engagement in HIV care or retentivity is less well understood. We hypothesized that depression could plausibly impair adherence and appointment attendance equally depression often manifests through loss of interest, poor concentration, poor motivation, reduced cocky-efficacy, fatigue, hopelessness, and suicidality [24, 26, 52]. However, in our study population depression was not associated with any of the retention indicators or viral suppression at half dozen months. Several studies conducted in Due south Africa, Kenya, and Uganda examining the clan betwixt depression prior to HIV testing and linkage to care had mixed results [32, 53, 54]. In S Africa, where linkage to care was defined as obtaining a CD4 count inside 3 months of a positive HIV test, ane written report found no deviation between those with and without depression at testing [53] and 1 found that those with depression were less likely to exist linked to care [32]. In Republic of kenya and Republic of uganda, greater depressive symptom severity was associated with greater likelihood of ART initiation during the study period among sero-converted partners of previously sero-discordant couples [54]. Studies of depression and memory in intendance conducted in Malawi and the Democratic republic of the congo institute no deviation betwixt 12-calendar month retention or viral suppression amongst pregnant women with and without depression at Art initiation [20, 55]. One explanation for the differences in the literature relating depression and ART adherence versus relating low and retentiveness is that low may not affect engagement in care in the aforementioned style information technology impacts Fine art adherence; different skills sets are required for adherence to daily Fine art than maintaining monthly clinic visits [53]. Further efforts to sympathize the relationship between depression and HIV will need to unpack the mechanisms through which depression impacts the different aspects of HIV care engagement.

Even so, the lack of association between low at ART initiation and whatsoever of the HIV outcomes in this study population is striking. Qualitative interviews with providers and patients conducted within the larger parent study during the screening phase of the programme, suggest that individuals identified with depression during the screening phase possibly received additional counseling on accepting their HIV status, Fine art adherence, and managing their low [56]. While these participants with depression did not receive evidence-based standardized depression treatment, information technology is possible that this additional attention may accept acted every bit an informal intervention. Equally such, this additional attending may have had a positive bear upon on HIV care engagement for depressed patients included in this analysis relative to those without depression.

Locally adapted, valid low diagnostic and direction tools are vital for addressing the brunt of low among people living with HIV. The implementation team chose the PHQ-9 for use among people living with HIV because information technology focuses specifically on depression, has been widely used and validated in many different cultures (including amid people living with HIV in SSA) [36, 37, 57], and works well both as a case identification tool likewise as a longitudinal monitor of response to handling. However, at the time, the PHQ-9 had yet to be validated in Malawi, though it has since undergone validation among a population of patients with diabetes [58]. Along that vein, cases of "depression" were identified with the PHQ-9 screening tool using a cutoff score of five and non a diagnostic interview. Information technology is plausible that some depressive symptoms were not actually features of a major depressive episode, merely rather a manifestation of milder syndromes, more than likely to resolve spontaneously and not crave an intervention. However, the sensitivity analyses using a cutoff score of x equally well as the recent validation study support our use and interpretation of the tool. Furthermore, the PHQ-9 was originally adult to be self-reported, but was administered by providers due to low levels of literacy among the patient population. Given the overlap in symptomology between HIV and depression itself, HIV providers may have identified an inaccurate brunt of low amid people living with HIV [59]. As this study relied on existing staff to screen patients for depression who were not incentivized to appoint in the depression screening programme, information technology is too possible that providers underdiagnosed cases of low. While a small sub-study comparing the providers' administration of the PHQ-9 to that of trained enquiry administration did find that research administration identified more cases of depression than providers, there was even so high overall agreement between providers and research assistants [sixty]. Yet, the accuracy of the PHQ-9 may have been compromised, given the mode of administration by existing staff (as opposed to self-reported) with varying degrees of commitment to the program. Tools such as the PHQ-9 would benefit from farther quantitative validation against a aureate standard diagnostic instrument to confirm their utility as part of task-shifting programs in SSA, particularly among people living with HIV.

Finally, complexities in measuring date and retention in HIV farther complicate the study of the role of depression in HIV care. Despite the importance of retentiveness to successfully treating HIV, there is no recognized "aureate standard" measure for retention in intendance [45]. A recent meta-assay highlighted some of the challenges around comparing studies examining the association between mental health disorder diagnoses and retention in HIV intendance, noting that "retentivity in care" may be operationalized to include measures of visit constancy, kept visits, no-show rates, and gaps in care [29]. In this study, memory overall was very low; but 30% of all participants remained continuously engaged in intendance through 6 months and only 43% attended an date after half-dozen months in intendance. Using Republic of malaŵi's definition of memory, overall 58% of participants were considered alive and in care at six months, though this is still lower than Malawi'due south 2018 12-calendar month retention estimates which found that 72% of adults who initiated ART were still in care at 12 months [61]. It is possible that we potentially underestimated retention in care due to "silent transfers," or individuals who decided to access intendance at a different location without formally transferring their records. In fact, the Malawi Ministry building of Health assumes that actual retentiveness is well-nigh ten% higher due to this misclassification of 'silent transfers' equally 'defaulters' in dispensary-based retention analysis, though a meta-assay of low- and middle-income state studies suggests retention may be equally much as eighteen% college [62]. Recognizing that this misclassification could take influenced all of the HIV intendance engagement measures, the charge per unit of silent transfer should not take varied between groups, so "silent transfers" should not have significantly biased comparisons betwixt those with and without low [61]. In this sense, "retention" in our study is tantamount to "memory at the specific clinic," and the information available may not yield a complete pic of date in care, limitations often faced by studies on memory in HIV care in SSA [63, 64]. Innovative methods and approaches for measuring retentiveness in intendance to manage these complexities are needed, particularly in low resource settings.

Limitations

Due to the implementation science nature of this study, the covariates captured were limited to routinely collected clinical data. Information technology is possible that the presented analyses were biased by unmeasured misreckoning factors such as stigma, socio-economic status, or transportation barriers. It is besides possible that we overestimated viral suppression as viral loads could merely be drawn from patients who remained in care and a large proportion of patients who did render for intendance were never sent for viral load testing.

Conclusion

This report documented a high prevalence of depression among patients newly initiating Fine art and low memory in intendance at 6 months. However, the examined HIV care outcomes at half dozen month were similar between those with and without depression. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms through which depression may undermine dissimilar aspects of the HIV care continuum, from testing through sustained retention and ultimately viral suppression.

References

-

Joint United nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS data 2019. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2019.

-

Frank TD, Carter A, Jahagirdar D, Biehl MH, Douwes-Schultz D, Larson SL, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2017, and forecasts to 2030, for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the global brunt of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2017. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(12):e831–e59.

-

UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An aggressive treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS; 2014. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-ninety-90_en_0.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2015.

-

Chirwa Z, Kayambo F, Oseni L, Plotkin M, Hiner C, Chitsulo C, et al. extending beyond Policy: reaching UNAiDS'Three "90" s in Malawi. Front Publ Wellness. 2018;6:69.

-

Dasgupta AN, Wringe A, Crampin AC, Chisambo C, Koole O, Makombe South, et al. HIV policy and implementation: a national policy review and an implementation example study of a rural area of northern Malawi. AIDS Intendance. 2016;28(9):1097–109.

-

Marsh Chiliad, Eaton JW, Mahy Thou, Sabin K, Autenrieth CS, Wanyeki I, et al. Global, regional and land-level xc–90–90 estimates for 2018: assessing progress towards the 2020 target. LWW; 2019.

-

UNAIDS. Turning Bespeak for Africa; an Historic Opportunity to Stop AIDS as a Public Health Threat by 2030 and Launch a New Era of Sustainability. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2018.

-

Haas Advertisement, Zaniewski E, Anderegg North, Ford Due north, Fox MP, Vinikoor M, et al. Memory and bloodshed on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: collaborative analyses of HIV treatment programmes. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(2):e25084.

-

Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler One thousand, Bender N, Egger Yard, Gsponer T, et al. Loss to program between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-assay. Trop Med Int Wellness. 2012;17(12):1509–20.

-

Estill J, Marsh One thousand, Autenrieth C, Ford Due north. How to attain the global 90–90-90 target past 2020 in sub-Saharan Africa? A mathematical modelling study. Trop Med Int Health. 2018;23(11):1223–xxx.

-

Wroe EB, Dunbar EL, Kalanga N, Dullie Fifty, Kachimanga C, Mganga A, et al. Delivering comprehensive HIV services across the HIV care continuum: a comparative analysis of survival and progress towards 90–ninety-90 in rural Malawi. BMJ Global Wellness. 2018;three(1):e000552.

-

Hall BJ, Sou Yard-L, Beanland R, Lacky M, Tso LS, Ma Q, et al. Barriers and facilitators to interventions improving memory in HIV care: a qualitative show meta-synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1755–67.

-

Bilinski A, Birru E, Peckarsky K, Herce M, Kalanga N, Neumann C, et al. Distance to care, enrollment and loss to follow-up of HIV patients during decentralization of antiretroviral therapy in Neno District, Republic of malaŵi: a retrospective accomplice study. PloS One. 2017;12(ten):e0185699.

-

Bulsara SM, Wainberg ML, Newton-John TR. Predictors of developed memory in HIV care: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):752–64.

-

Friedrich M. Depression is the leading cause of disability effectually the earth. Jama. 2017;317(15):1517.

-

Tsai Air-conditioning. Reliability and validity of depression assessment among persons with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2014;66(5):503.

-

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass JK, Alexandre P, Mills EJ, Musisi Southward, Ram M, et al. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS and behavior. 2011.

-

Kim MH, Mazenga AC, Devandra A, Ahmed S, Kazembe PN, Yu X, et al. Prevalence of depression and validation of the brook depression inventory-Ii and the children's depression inventory-short amidst HIV-positive adolescents in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(ane).

-

Malava JK, Lancaster KE, Hosseinipour MC, Rosenberg NE, O'Donnell JK, Kauye F, et al. Prevalence and correlates of probable depression diagnosis and suicidality among patients receiving HIV care in Lilongwe, Malawi. AIDS patient care and STDs. Nether Review.

-

Harrington BJ, Hosseinipour MC, Maliwichi 1000, Phulusa J, Jumbe A, Wallie S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of likely perinatal low among women enrolled in Option B+ antenatal HIV intendance in Malawi. J Touch Disorders. 2018.

-

Dow A, Dube Q, Pence BW, Van Rie A. Postpartum depression and HIV infection amid women in Malawi. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2014;65(3):359–65.

-

Bernard C, Dabis F, de Rekeneire Due north. Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic Review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2017;12(viii).

-

Abas M, Ali GC, Nakimuli-Mpungu Eastward, Chibanda D. Low in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: time to human activity. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(12):1392–half-dozen.

-

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Low and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-assay. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2011;58(ii):181–7.

-

Pence BW, Miller WC, Gaynes BN, Eron JJ Jr. Psychiatric affliction and virologic response in patients initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Allowed DeficSyndr. 2007;44(ii):159–66.

-

Kidia Chiliad, Machando D, Bere T, Macpherson Grand, Nyamayaro P, Potter L, et al. 'I was thinking too much': experiences of HIV-positive adults with common mental disorders and poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Republic of zimbabwe. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(7):903–13.

-

Smillie Thou, Van Borek North, van der Kop ML, Lukhwaro A, Li Northward, Karanja S, et al. Mobile health for early retention in HIV care: a qualitative written report in Kenya (WelTel Retain). Afr J AIDS Res. 2014;13(4):331–eight.

-

Franke MF, Kaigamba F, Socci AR, Hakizamungu Grand, Patel A, Bagiruwigize E, et al. Improved retentivity associated with community-based accompaniment for antiretroviral therapy commitment in rural Rwanda. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(ix):1319–26.

-

Rooks-Peck CR, Adegbite AH, Wichser ME, Ramshaw R, Mullins MM, Higa D, et al. Mental health and memory in HIV care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37(six):574.

-

Rane MS, Hong T, Govere S, Thulare H, Moosa Thousand-Y, Celum C, et al. Depression and feet equally take chances factors for delayed care-seeking beliefs in human immunodeficiency virus–infected individuals in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2018:ciy309.

-

Turan B, Stringer KL, Onono Thou, Bukusi EA, Weiser SD, Cohen CR, et al. Linkage to HIV care, postpartum depression, and HIV-related stigma in newly diagnosed meaning women living with HIV in Kenya: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;fourteen(one):400.

-

Ramirez-Avila 50, Regan S, Featherbrained J, Chetty South, Ross D, Katz JN, et al. Depressive symptoms and their impact on health-seeking behaviors in newly-diagnosed HIV-infected patients in Durban. South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2226–35.

-

Walkup J, Wei W, Sambamoorthi U, Crystal S. Antidepressant handling and adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among patients with AIDS and diagnosed low. Psychiatr Q. 2008;79(1):43–53.

-

Hawkins NG, Sanson-Fisher RW, Shakeshaft A, D'Este C, Green LW. The multiple baseline design for evaluating population-based enquiry. Am J Prevent Med. 2007;33(2):162–viii.

-

American Psychiatric Clan. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th (text revision) edition. Washington, DC; 2000.

-

Cholera R, Gaynes B, Pence B, Bassett J, Qangule North, Macphail C, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-ix to screen for depression in a high-HIV brunt primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg. South Africa. J Affect Disorders. 2014;167:160–6.

-

Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong'or WO, Omollo O, et al. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales amidst adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Republic of kenya. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):189.

-

Malava JK, Lancaster KE, Hosseinipour MC, Rosenberg NE, O'Donnell JK, Kauye F, et al. Prevalence and correlates of probable depression diagnosis and suicidality among patients receiving HIV care in Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2018;30(4).

-

Kroenke Thousand, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief low severity measure. Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–xiii.

-

Stockton M, Udedi K, Kulisewa K, Hosseinipour M, Gaynes B, Mphonda S, et al. The impact of an integrated depression and HIV treatment program on mental health and HIV care outcomes amongst people newly initiating antiretroviral therapy in Malawi PLOS One. 2020.

-

Udedi M, Stockton MA, Kulisewa K, Hosseinipour MC, Gaynes BN, Mphonda SM, et al. The effectiveness of depression management for improving HIV intendance outcomes in Malawi: protocol for a quasi-experimental written report. BMC Publ Health. 2019;19(1):827.

-

Malawi Ministry building of Wellness. Malawi Guidelines for Clinical Direction of HIV in Children and Adults. Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health; 2016. p. 2016.

-

Relief PsEPfA. Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting (MER two.0) Indicator Reference Guide Version two.iii. Washington (DC): PEPFAR; 2018.

-

Joint Un Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global AIDS Monitoring 2019: Indicators for Monitoring the 2016 Political Declaration on Catastrophe AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2018.

-

Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, Davila J, Drainoni Thou-L, Gardner LI, et al. Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard. J Acquir Allowed DeficSyndr. 2012;61(five):574.

-

Wu P, Johnson A, Nachega B, Wu B, Ordonez C, Hare A, et al. The combination of pill count and cocky-reported adherence is a strong predictor of first-line Art failure for adults in Due south Africa. Curr HIV Res. 2014;12(5):366–75.

-

Earth Wellness Organisation. Acting WHO clinical staging of HVI/AIDS and HIV/AIDS example definitions for surveillance: African Region. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2005.

-

Van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of detached and continuous data past fully conditional specification. Statist Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219–42.

-

White IR, Royston P, Forest AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: problems and guidance for exercise. Statist Med. 2011;30(4):377–99.

-

Von Hippel PT. How to impute interactions, squares, and other transformed variables. SociolMethodol. 2009;39(1):265–91.

-

Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in depression-, middle-and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):291–307.

-

Losina East, Bassett Four, Giddy J, Chetty Due south, Regan Southward, Walensky RP, et al. The "ART" of linkage: pre-treatment loss to care afterward HIV diagnosis at two PEPFAR sites in Durban, South Africa. PloS One. 2010;five(iii):e9538.

-

Cholera R, Pence B, Gaynes B, Bassett J, Qangule Northward, Pettifor A, et al. Depression and engagement in intendance amidst newly diagnosed HIV-infected adults in Johannesburg South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1632–40.

-

Velloza J, Celum C, Haberer JE, Ngure K, Irungu E, Mugo N, et al. Depression and Art initiation amid HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2509–18.

-

Yotebieng KA, Fokong K, Yotebieng G. Low, retention in intendance, and uptake of PMTCT service in Kinshasa, the Democratic Commonwealth of Congo: a prospective accomplice. AIDS Intendance. 2017;29(3):285–9.

-

Stockton Thou, Ruegsegger L, Kulisewa G, Akiba C, Hosseinipour K, Gaynes B, et al. "Depression to me means…": Cognition and attitudes towards depression among HIV care providers and patients in Malawi. JIAS. Under Review.

-

Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma South, Deyessa N, Bahretibeb Y, Shibre T, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in E Africa. Psychiatr Res. 2013;210(two):653–61.

-

Udedi Yard, Muula Every bit, Stewart RC, Pence BW. The validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-nine to screen for depression in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry. Under Review.

-

Yun LW, Maravi M, Kobayashi JS, Barton PL, Davidson AJ. Antidepressant treatment improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy among depressed HIV-infected patients. JAIDS J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2005;38(iv):432–viii.

-

Pence BW, Stockton MA, Mphonda SM, Udedi M, Kulisewa Grand, Gaynes BN, et al. How faithfully do HIV clinicians administrate the PHQ-nine depression screening tool in loftier-book, low-resources clinics? Results from a depression handling integration project in Malawi. Global Mental Health. 2019;6.

-

GoMMo Health. Integrated HIV Program Report Oct-Dec 2018. Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health; 2019.

-

Wilkinson LS, Skordis-Worrall J, Ajose O, Ford N. Self-transfer and bloodshed amidst adults lost to follow-up in ART programmes in low-and centre-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;twenty(3):365–79.

-

Geng EH, Nash D, Kambugu A, Zhang Y, Braitstein P, Christopoulos KA, et al. Memory in care amid HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings: emerging insights and new directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):234–44.

-

Clouse G, Phillips T, Myer 50. Agreement data sources to measure patient retention in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa. Int Wellness. 2017;9(4):203–5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the participants who allowed their clinical information to be used for this assay, the research assistants who worked tirelessly to abstract said clinical data, and our astonishing project coordinator (SM) without whom this study would non have been possible. Finally, this study was funded by the generous support of the American people through the Usa President'southward Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEFPAR) and United states Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Cooperative Agreement Project SOAR (Supporting Operational AIDS Inquiry), number Help-OAA-A-xiv-00060. The contents in this publication are those of the authors and practice not necessarily reflect the view of the PEPFAR, USAID, or the United States Government.

Funding

This study was funded through the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEFPAR) and United states Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Cooperative Agreement Project SOAR (Supporting Operational AIDS Research), Number AID-OAA-A-14-00060.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Disharmonize of interest

The authors declare that they accept no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approving

Institution review board (IRB) blessing was obtained from both the Republic of malaŵi MOH's National Wellness Science Enquiry Committee (NHSRC) IRB and the Biomedical IRB of the University of N Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Boosted information

Publisher'southward Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you lot give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables licence, and signal if changes were fabricated. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the commodity'southward Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article'south Artistic Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilise, you will demand to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stockton, M.A., Gaynes, B.North., Hosseinipour, M.C. et al. Association Between Depression and HIV Care Engagement Outcomes Among Patients Newly Initiating Fine art in Lilongwe, Malawi. AIDS Behav 25, 826–835 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03041-seven

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03041-seven

Keywords

- Depression

- HIV

- Retention

- Viral suppression

- Sub-saharan africa

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-020-03041-7

0 Response to "Treatement of Depression Among Peaple Life With Hivaids on Art"

Post a Comment